Blackout Records was a mostly punk and hardcore label started by Bill Wilson and Jim Gibson in the NYC suburb of Yonkers, and the Bronx campus of Fordham University, in 1988. It has been a few years since we have seen a new release from the label but with the recent announcement of the “Sheer Terror The Bulldog Box” coming in 2016 things could come back to life. We figured this would be a good time to catch up with Bill Wilson and ask him about this new upcoming release, the labels rich history as well as what this all could mean for future Blackout Records releases. Interview conducted February 2016.

IE: Hey Bill. It's been like what? 12 year’s now since we've seen an official Blackout release? Please start off by telling us what you've got in the works at the moment and why the time was right to do this?

Bill: Yeah, it's been a long time. Back in 2004, the label kind of ended with a whimper, mostly due to partner infighting, and it wasn't fun anymore. But as my indie PTSD has subsided, vinyl has surged back, and demand for some of the catalog still being pretty high, I thought it would be great to give some of it a final-go around in the same spirit I did the original few releases.

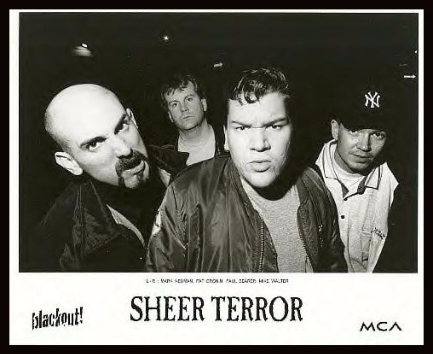

IE: First up with this comeback of sorts is a Sheer Terror box set containing a bunch of different albums and other goodies. Can you go a little more into detail as to what the “Bulldog Box” will have in it and when can people expect to see it out?

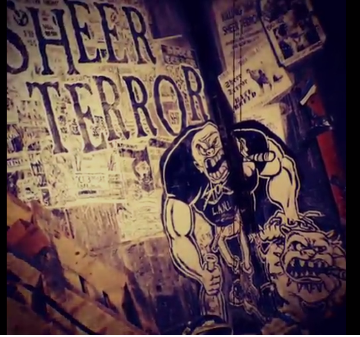

Bill: It's probably no secret that Sheer Terror was probably my reason for starting the label, so it's fitting that I kick it all off with the box set I always wanted to make. “Sheer Terror: The Bulldog Box” has five records all exclusive in some way to the box. They include classics such as “Just Can't Hate Enough”, “Thanks Fer Nuthin'” and “Old New Borrowed And Blue”. It also has never-before on LP pressings of the “No Grounds For Pity” demos and rarities, and a never-before-heard only pressing of alternative versions of “Love Songs”... tracks called “Unheard Unloved” that are much more raw than the album that came out. What's fun about it is I got old friends of the band to come back and help. Sean Taggart did a cool installation in my garage featuring his old Shok skinhead illustration that became the cover for the “No Grounds”... LP. Wes Harvey (who did the infamous guillotine scene for the live 7" and shirts) is doing the brand new cover for the box. There are also some other cool things in the box such as a patch and booklet. So I think any fan of the band will find this box to be a great experience. It will be available PRE-ORDER only and won't be in stores. The orders will go live in the next few weeks, so people should track @blackoutnyhc on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram to get the update. When they sell out, they sell out.

IE: Would you say then that your looking to bring Blackout back for another lengthy run or is this just a one and done type of deal... or would you say this is a wait and see type of thing where you are still undecided as to the future of the label?

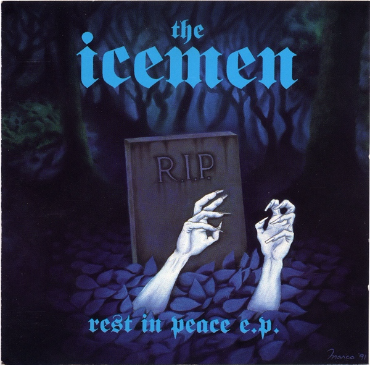

Bill: Totally undecided. I definitely have one more project after this. Possibly another after that. Breakdown is doing the vinyl of the demo themselves, I licensed the H2O vinyl to Bridge 9 a few years ago. My buddy Jim Gibson did an LP pressing of “Where The Wild Things Are” a few years ago as well. Marco from the Icemen requested that I not release that single anywhere. As far as new bands, I completely confess I'm out of touch. My professional life in music has taken me in a much different direction, and my taste is far more eclectic than it was when I was 19, angry and bald.

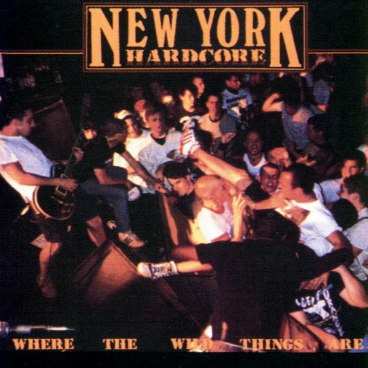

IE: 1989's “Where The Wild Things Are” compilation is the labels first release and got Blackout on the map. Can you take us back to the time leading up to its release and give us some background as to how you came up with the idea for this now legendary compilation?

Bill: I grew up with Carl from Breakdown/ Raw Deal/ Killing Time, we've known each other since we were in nursery school. Our parents became friends, so we wound up pretty much going to the same schools all the way through college. Eventually he got together with a few guys to form Breakdown and it took off. Going to shows as their hanger-on/ roadie was really how I started to get to know people, and that made it easier. We were all fans of Sheer Terror as well, and at some point we realized that we went to Jr. High with Paul Bearer. At the time, I didn't do drugs or drink but was loathe to call myself straight edge. Even though as individuals, some of the guys were cool- I kind of hated the whole Youth Crew, whitewashed, self-righteous jock bullshit. So I decided I'd like to start a label being the Yin to Revelations Yang.

IE: Do you remember the circumstances back then that led you to want to start your own label? Can you remember when the actual idea hit you and what actually sparked it?

Bill: Just being a fan and consuming is pointless to me. Being a productive part of the community, what people might even call entrepreneurship, is what it's about. So I started illustrating flyers and shirts for bands, like the Breakdown "brick" logo. One day I was with Drago from Breakdown and a few others and mentioned I should do a label, and they all thought I should. So getting tracks wasn't hard as most were friends-of-friends. I had a basic business school background from my college coursework, but had to learn graphic design (desktop publishing wasn't around then) myself. I learned how a record was supposed to be made using a book I found at See/Hear called “How To Make And Sell Your Own Record” by Diane Rappaport as my bible. My buddy Jim Gibson and I pooled our money, pressed it- and "kapow". Blackout! was born. I still remember us getting thrown out of Bleecker Bob’s when we brought it down the first time.

IE: I think everyone who sold records and zines has a Bleecker Bob story as he was definitely not easy to deal with. What exactly happened?

Bill: Jim and I were very excited when we finally got the first pressing in. So we filled up the car and immediately drove downtown to Venus Records, Bob's etc. The guys at Venus were effusive- as happy as we were almost to finally get it and paid cash. Bob, being the human being he was (actually I think he's still alive) started bitching about paying up front, so I told him to screw off in so many words. He didn't like that and threw me out. Jim stayed behind and then Craig, the tall skinhead that worked there, came back- whispered to Bob, and all of a sudden we were his bestest friends. Funny how that works. After that, I never had a problem with Bob.

IE: In the earliest stages of Blackout Records how hands on were you with putting out albums? The bands obviously supplied you with the music but what else did it take on your end to get everything else taken care of?

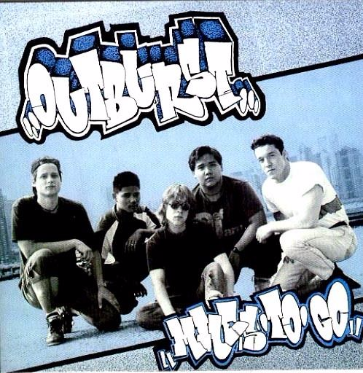

Bill: My 89 year old Sicilian grandmother stuffed Outburst singles into covers on more than one Sunday. My dad helped me do my taxes. But I can fully say that I did pretty much everything else myself. Like I said before, I did all graphic design for the first few records with old-school paste-up. All the ads, posters, covers, booklets, etc. were all done on giant pieces of paper with letraset, and blue, camera ready pens. Photos had to be shot using a "line screen" so they could appear in print clearly. I corresponded with people using snail mail, not email and I had a phone, on my desk with an answering machine- calling record stores, fanzines, college radio (using lists stolen for me from Caroline or Relativity).

IE: How many actual copies were being sold on the earliest releases? Were you making money off the label or were you running it almost as a hobby and possibly losing a lot of your own money?

Bill: I'd say the compilation sold about 15,000 copies originally. But making money was always a joke. Most of that was cash flow. A distributor would order 1,000 but not pay for the previous 1,000. So I would use credit cards to pay for another pressing, hoping that the payment would come in before the month was over. Sometimes you got screwed, or the distro went out of business, leaving you high and dry. So it was always a fucking grind. When I was in school, it gave me some spending money sometimes (usually after selling stuff direct at shows) but most often it's head was only just above water, and anything was put back into trying to do more things. After I graduated, I got a job in the music business so I could keep doing my label. I worked at RED, Caroline, and was general manager for the US office of a very successful metal label called Earache for a year or so back in the early 90's. But all of those were secondary to my real dream of making Blackout sustainable.

IE: Who were the bands easiest to work with and which ones proved to be a little more difficult?

Bill: Anyone emotionally invested in what they do as art is always in some degree of conflict with the people who are trying to do their own business that they are emotionally invested in. Finding that balance is important. Finding that balance when you're 20 is even more challenging. Just like politics, you can't reason around emotionally based arguments. So any negative experiences usually came from that. I will say that probably one of my best experiences overall with a band was with The Goops. a female-fronted punk band that did really well, played a tour or two with Rancid, and got a video on MTV. They were 100% driven, professional, and incredibly fun people to be around.

IE: When you look back to the early days of Blackout was there a hardcore band (or bands) that you really wanted to sign but could not get them for whatever reason?

Bill: Not many. I wanted to sign the Dropkick Murphy’s after seeing them play in Boston at some early show. Underdog was supposed to be on the “Where The Wild Things Are” compilation but didn't wind up there for a reason I do not remember.

IE: Where did the name Blackout Records come from?

Bill: No light. No hope. No future. It's what was in my head at the time.

IE: Blackout's later years saw you move away from NYHC bands and saw you go more in a direction I guess of more punk and underground rock etc. Without getting too overboard on the labels history can you take us through the... I guess transition from Blackout the NYHC label to Blackout the underground punk and underground rock label?

Bill: Part of the decision was based on the fact that I moved to Manhattan and decided I liked shows with girls at them WAY more than clubs where a bunch of humorless fat dudes that I didn't know would fight each other. The hardcore records that I put out were from friends, from the heart, and nothing from that era was speaking to me at the time. It seemed derivative. CBGB late night, Coney Island High and Don Hill's were about 10x more fun. AmRep, Matador, SubPop, Touch and Go all became what I was listening to. So that's why I headed off in those directions and started the short-lived Engine label that did a Guided By Voices EP among other cool records like The New Bomb Turks. Great bands. Great fun.

IE: I'm guessing financially Blackout was more successful when this change over became the labels main focus. Am I correct?

Bill: I was getting smarter at the business side- being fucked over has that magical effect but cash was always an issue. Without a secondary job, I would not have been able to have an apartment in NYC. Eventually I had the ability to have one person, Carl, on "staff" and a few interns working from his loft on Grand St.

IE: In the mid-1990s you had Sheer Terror on Blackout and a deal was struck with MCA Records where they moved over to MCA. What kind of hand did you have in that? I don't recall a lot of the actual details from that but I do remember it was not a match made in heaven for all parties involved. Can you talk about that and what were the perks and disappointments with that deal?

Bill: The MCA thing came about because I was friendly with my A&R guy, Hans. We had worked together at Relativity. He really loved some of my bands and always tried to help me out. After leaving Relativity, he landed at MCA, which was looking to "farm team" some bands during the great indie land grab of the late 90's. They gave my label what was called a "first look" deal. That means, in exchange for an annual sum of money, they could take over the contracts of my bands, provided the band wanted to. I'd get an additional sum of money, plus a royalty override on the major record. As part of the deal, they also gave me an office and my guys to work out of their office at 1755 Broadway. At that point The Goops had already been spoken for by Reprise and were recording their debut for them. Sheer Terror were looking around, seeing other bands "successes" and essentially said "Do this or we break up." So Hansel and I convinced the powers that be at MCA to do it. In hindsight, they were not remotely the right band for a major label and I have no idea what I was thinking. It was all fucked up, but that part of it is all in the Sheer Terror DVD. It was during that time I signed H2O for their debut album, which is my most successful record to date. Then Kill Your Idols, so things were good for a while....

IE: What have you been up to in the past 12 years since we last saw you put out some new music with Blackout? Do you have any hobbies?

Bill: I was in limbo for a year or so after the label shut down. It was pretty traumatic to quit my dream- but after a while it was liberating. I found my way into the burgeoning tech/startup scene in New York, found a few gigs at some music startups, then got a gig at Atlantic Records. While I was there got to meet and work with great people in the digital, global business and operations area of the company, which set me up for my next role. For the last 7 years I have been Vice President of Digital Strategy of MusicBiz (formerly NARM) a music industry trade organization whose board members include Amazon, Apple, Microsoft, and Spotify. I do a lot of work on what many people would consider highly technical and very boring. I also consult for a few tech startups on the side. So I'm still very much in the music business, just not remotely on the creative side. My upside is I get to travel all over the world, and talk about cool shit with people smarter than me. On the personal tip, I have 3 dogs and am an advocate for American Pit Bull Terrier. My girlfriend and I do lots of rescue/support stuff like transports. Blackout! is apparently my new hobby...

IE: You were telling me that the label became not fun to do anymore right before you stopped doing it. When you did stop putting out releases and you had time to think back about the 15 or so years you did run it what were some of the better stories or memories that you had?

Bill: Money was always an issue. Finding ways just to put bands in the studio, keep them on the road, keeping stock pressed, all of those things make shit very stressful, all the time. When MCA went under, so did my deal. I sold records from the basement of a house I rented and was able to keep up the bills. But then I got into a series of desperate, bad partnerships that just became more acrimonious than any argument with any band ever. Calling the game was the best thing I did for myself, I just regret I didn't do it sooner. To paint all of that with that depressing brush discounts all the fucking fun I had. The travel, the tour shenanigans- it was like joining the circus. But that circus also gave me a career path, I got to hang with fantastic freaks around the world, and people that I've forged decades-old friendships worth. It may not have been financially viable but it certainly was worth every drop of sweat and every tear.